Few topics spark as much controversy in the climate debate as the assertion that we need to cut our meat consumption if we want to reach our climate targets. On some primal level going for the burger on your plate is a much more outrageous act than going for your car. So it’s no surprise that technical-minded people have been looking for a panacea in the form of lab-grown meat. And the pitch is alluring: If the plan works out the burger is safe and we get to reduce our emissions. We get to have our cake and eat it, too.

However that “if” is doing a lot of work in this sentence. So today we will have a look at the bear take on lab-grown meat: It might be viable at some point but too late and too ineffectual to be considered a Climate Solution. Even worse: It could distract from the real issue much in the same way that CDR (Carbon Dioxide Removal) is already being used by Big Oil to prevent actual mitigation.

But before we get there we need to establish why we need to urgently reduce our dependence on livestock farming.

We can’t meat two degrees

This section is entirely based on the IPCC AR5 report on food security (Chapter 5). The IPCC reports are the authoritative scientific meta-reviews of all things climate.

Let us start by ripping off the band-aid: Livestock farming is a major driver in deforestation and methane emissions causing about 15% of human greenhouse gas emissions (source). This means we need to drastically reduce the emissions from this sector if we want to have a realistic shot at achieving our climate goals. There are a few nuances here to be aware of:

Not all meat is created equal. Cattle are a complete outlier, accounting for 65–77% of livestock-based emissions. Even in the absence of climate change, they are pretty inefficient. For example, one study found that “replacing beef in the USA diet with poultry can meet the caloric and protein demands of about 120 to 140 million additional people consuming the average American diet” (IPCC AR5 5.3.4).

Our world in data chart: Food emissions across the supply chain. Meat in general but especially beef is at the top.

Not all carnivores are created equal. While most cattle emissions are generated in developing countries, they are not the ones to benefit. Citizens in developed nations consume on average four times as much dairy and three times as much meat than those living in developing nations. This means that not only should richer countries lead the charge on this issue, but it also implies that any meat substitute must be affordable on a global scale.

Our world in data chart: Countries and their meat consumption vs their gdp per capita.

It’s not just the climate. Meat and dairy also exert pressure on increasingly unstable freshwater resources. Beyond that, there are well-known issues regarding health and the ethics of industrial farming.

You don’t have to go fully vegan. As you can see in the graph below even moderate reductions can go a long way. With a shift in culture and an increase in substitute products, cutting down on meat has never been easier. However, the cattle industry has taken a page from big oil and is currently waging an all-out public relations war against any type of regulation.

The emission mitigation potential of various diets.

This is where the argument for lab-grown meat comes into play: We need to get people to switch, but the threshold seems high. So let’s offer them a product that is nearly identical but can be powered by green energy.

Can we grow our way out of this?

Sofar lab-grown meat has arguably followed the trajectory of many paradigm-shifting technologies: While the first public trial for a single beef patty cost $300,000 in 2013, startups and billions of funding have since managed to wrangle the price below $100. There is no doubt that this is an exciting consumer product backed by a wealth of money, talent, and interest. However, the only question in the climate context is whether or not they can significantly mitigate meat-based emissions within the next ten to twenty years or so.

The answer to that question is: No. It is very unlikely that lab-grown meat will achieve anywhere near the economies of scale needed to make a reasonable dent in global meat consumption. According to Joe Fassler who wrote an excellent article on this question in thecounter, the outlook might be even more dire:

“Splashy headlines have long overshadowed inconvenient truths about biology and economics. Now, extensive new research suggests the industry may be on a billion-dollar crash course with reality.” - Joe Fassler, thecounter

While I highly recommend that you read the article I will now briefly summarize how he arrived at such an extreme conclusion.

It doesn’t scale. One of the chief proponents of lab-grown meat, the Good Food Institute (GFI), commissioned a techno-economic analysis (TEA) to project what the production of cell-cultivated meat in 2030 might look like. They imagine a facility that would use huge bioreactors to produce 10,000 metric tons of meat per year at an upfront capital cost of $450 million. 10,000 metric tons might sound like a lot until you learn that it would only amount to 0.02% of meat production in the US. Further, due to the high capital expenditure, investors would have to lock themself into 30-year repayment terms to keep the price per kilogram competitive - this is why supporters of the technology are calling for substantial public investments. So investors are faced with the “choice” of either throwing away absurd amounts of money to maybe make the tiniest dent in our meat production or to make a profit with a niche luxury product.

It might not even work. Even if they get built, these plants might not ever actually end up producing these quantities of meat. While animal cells double at a rate of once every 24 hours, bacteria do so once every 20 minutes. This means that these facilities effectively require a pharma-grade sterile environment to prevent minor contaminations from ruining days and tons worth of cell cultures. The entire pharma industry currently boasts a bioreactor volume three times as large as the facility imagined but composed of much smaller installations. No one knows if it is even possible to do this at the proposed scale and it might not even end up working at all.

Or to quote Dr. Humbird the lead author of another industry-funded TEA: “Clearly, I don’t think cultured meat has legs […] I think I make that clear in the paper, if not in such colloquial terms. But it seems like a bunch of hooey to me.”

People might still reject it. The key selling point of lab-grown meat is that it aims to taste just like the real deal, without all the downsides. But taste alone might not be enough to win everyone over. Even if we nail the technical aspects, there’s evidence to suggest that a sizeable chunk of people won’t make the switch. It turns out that when people don’t reduce their meat consumption they do so for a variety of cultural and economic reasons, taste just being one of them. This is before we even get into legitimate health concerns or the potential of anti-tech social panics such as those that we saw during the pandemic.

We already have the tools

Okay, so it seems that lab-grown meat has some issues that might prevent it from being a player in the landscape of Climate Tech. But do we have alternatives and if so how are they doing? Yes, we do, but unfortunately, we are not on track to meet our goals.

Graph showing that our reduction in food based emissions are off target by a factor of 5.

Figure showing the projected vs needed reduction in ruminant meat consumption to reach our climate goals. We need to accelerate by a factor of 5. Policy. As with all things climate-related the key lies in pricing in the negative externality which means covering meat and dairy under existing or new carbon pricing schemes. There are however quite a few political challenges here that need to be overcome with carefully crafted policy: Revenues need to be appropriately recycled to consumers so as to not make meat eating a privilege of the rich. Further, agricultural lobbies - which hold a lot of sway in the EU for instance - must be carefully involved in order to prevent them from blocking the process outright.

In the meantime, governments might opt for more indirect yet targeted measures such as the upcoming EU Deforestation regulation which flat-out bans products that have caused any form of forest degradation. Soft measures such as awareness campaigns and subsidies for alternatives are also a part of the mix.

Market. The good news is that we are already starting to cut down on our livestock emissions. It is just not happening fast enough. While there is both a strong cultural momentum and an explosion of meat substitute products more effort is needed. Stay tuned for an in-depth analysis here at ClimateDrift.

To summarize; while the solutions we have are imperfect they completely outmatch lab-grown meat for the simple virtue that we know their issues while the former is full of unknowns. Beyond that, we can already measure the GHG impact of alternatives in megatons of CO2 equivalents which cannot be said for lab-grown meat.

It’s not a Climate Solution

Now advocates of lab-grown meat will have a few objections to the points I raised earlier which I will address here:

We tend to be myopic when it comes to frontier innovation. Just look at the price drop of DNA sequencing or solar panels!

As Skander has pointed out before not every technology is solar panels. In fact, we have also heard this argument being made for crypto, self-driving cars, or going to Mars. Sure they might overpromise for years and some of them might end up changing the world. Once lab-grown meat beats all the odds I will happily attach a clarification to this article. But when it comes to the climate this is a bet we cannot afford to make, especially, in the presence of superior alternatives.

It does not have to be this black and white. We can push for dietary changes while still advocating for lab-grown meat.

While I agree that progress is not a zero-sum game the same cannot be said for the amount of political willpower and investment available for fighting climate change. Every inch of legislation is currently hard-fought and the resulting public budgets are thus limited. Even worse; governments that are being lobbied by big meat might be tempted into using public investments in lab-grown meat as a way to greenwash their policies. We are seeing this play out with CDR, so it is not as unlikely as you might think.

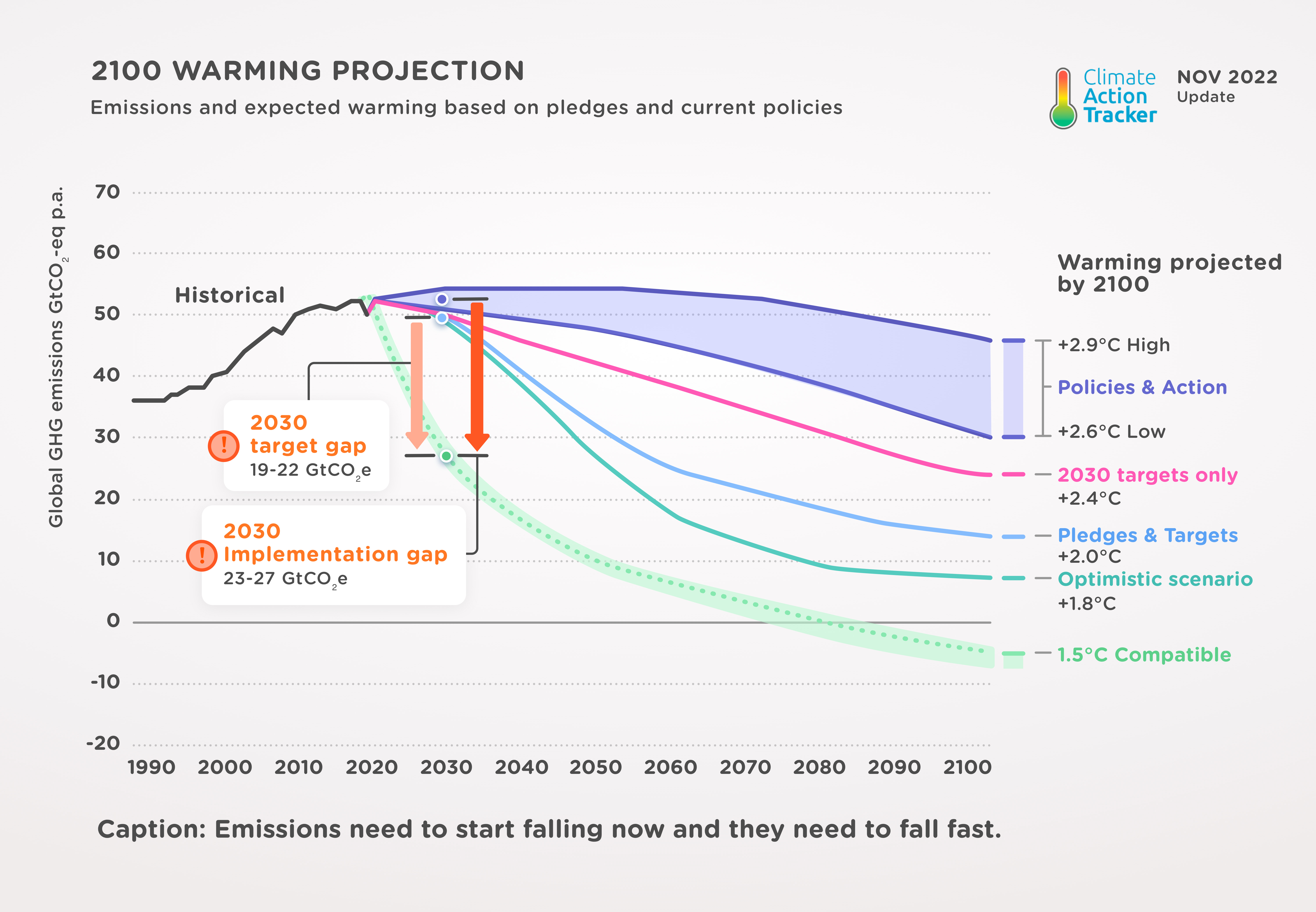

Climate action tracker chart highlighting that drastic emission reduction is needed to reach the 2 degree target.

2100 warming projections given different scenarios. The graph shows that there is a significant gap between both implementations and pledges and reductions that are actually needed to achieve “positive” scenarios such as the 1.5 degree target. Emissions need to start falling now and they need to fall fast. To sum it up: Lab-grown meat is not a climate solution because it seems very unlikely that it can mitigate farming-based GHG emissions. It would be different if it were our only option, but it’s not. None of this is to say that this is not an interesting niche product that you can be excited about. But we must be careful about what we promote as “Climate Tech” because it impacts the way we allocate both private and public funding. The stakes are simply too high.